One Grenade and a Million What-Ifs—Wondering What Might Have Been for Milton Lee Olive III

It’s almost Veterans Day, not Memorial Day, but the real timing of this essay has to do with a birthday.

Milton Lee Olive III would have turned seventy-seven on Tuesday if he hadn’t thrown himself on a grenade nearly six decades ago.

His life was bookended by a violent end and a violent beginning, with not quite nineteen years in between. In the in-between, he went to school and he went to church, he snapped photographs, and he wrote love letters.

The beginning took place in the South Side of Chicago on Nov. 7, 1946. Olive was a breech birth, and both of his arms were broken when he was turned around. A few hours later, his mother, Clara Lee, started to hemorrhage; she died later that day. Milton’s father gave his son the middle name of Lee in her honor.

The end happened in the jungles of Vietnam on Oct. 22, 1965. Dropped by helicopter into a battle zone near Saigon, Olive’s unit was ambushed while chasing a band of Viet Cong. Olive and four other men dove to the ground behind some burned-out tree stumps and were lying face-down in the dirt when an enemy soldier lobbed a grenade into their group, where it landed about a foot away from 1st Lieutenant Jimmy Stanford’s face.

There are at least three versions of what Olive shouted, depending upon whom you ask—either “I’ve got it!” or “Look out, Lieutenant, grenade!" or "Look out, Hop, grenade!” But there’s only one version of his actions.

Olive grabbed the live grenade, hugged it close, and fell on it to absorb the blast.

In doing so, he saved the lives of Stanford, who was the platoon leader, John “Hop” Foster, Vince Yrineo, and Lionel Hubbard. If Private First Class Olive did shout a warning to Stanford, it was the first and only verbal interaction they had; Stanford had joined Company B of the 173rd Airborne Brigade just a couple of days earlier, and the two had not yet spoken.

For his actions, Olive became the first Black soldier awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in the Vietnam War, the military’s highest honor.

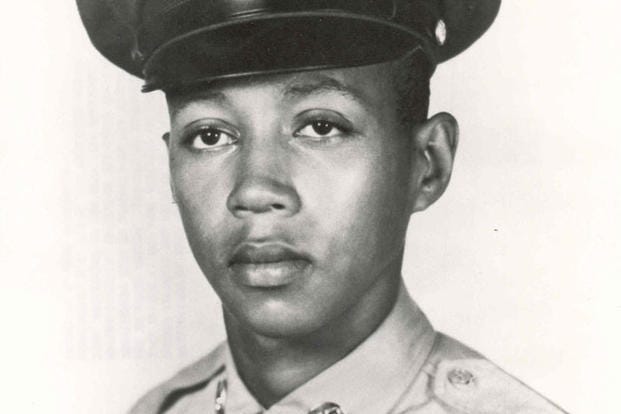

We’re left to wonder what kind of life a man like Olive might have lived, left to imagine where his brief trail of breadcrumbs might have led. It’s impossible to know, of course, but it’s also impossible not to wonder what-if when reflecting upon a teenager who didn’t hesitate to grab that grenade. He looks strikingly young in his official U.S. Army photos, and I wonder whether his cheeks had felt a single stroke of a razor. Where was his life headed?

I want to know, too, why he’s not famous, why there’s no movie.

“I would be the first cat in line if there was a film about a real hero, you know, one of our blood. Somebody like Milton Olive,” the character Otis says in the Spike Lee movie Da 5 Bloods, a film about four Black veterans who return to Vietnam decades after the war to find their squad leader’s remains and a stash of buried gold.

A Black man, Olive had run into racism plenty of times stateside and again in Vietnam. At base camp, he met a soldier raised in segregated South Carolina who grew up believing the South would rise again. The two men provoked each other, said the southerner, Robert Toporek, until one day they headed behind a tent to settle it with fists.

“It was a draw and we hugged,” Toporek told StreetWise magazine in 2021. “It was the only thing left to do. The only thing left was two men whose lives depended on each other.”

Stanford, the white platoon leader, arrived in Vietnam unhappy with the government’s decision to integrate the armed forces. Although President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order in 1948 to formally desegregate the U.S. military, Vietnam was the United States’ first fully integrated war. Many units were still segregated during the Korean War, particularly in the Army.

Stanford’s great-grandfather was a Confederate soldier, and Stanford grew up in a segregated town in Texas where he didn’t see Black people out after dark. He still mixed the n-word into conversation. Racial tension, he told the Chicago Tribune, was a way of life.

“That's what I grew up with,” Stanford told the newspaper. “That's what I knew. I learned that at home, and it was like learning how to put on your clothes.”

We’re left to wonder what kind of life a man like Olive might have lived, left to imagine where his brief trail of breadcrumbs might have led. It’s impossible to know, of course, but it’s also impossible not to wonder what-if when reflecting upon a teenager who didn’t hesitate to grab that grenade.

That day in Saigon, lying on the ground getting fired upon and returning fire, Stanford was the only white man.

The group included three Black men—Olive, Foster, and Hubbard—and a Mexican-American, Yrineo, who had called out Stanford days earlier for using a racial slur.

Stanford said that day changed his thinking, that he determined to make sure the world didn’t forget about Milton Olive III. He even served a four-year assignment in the Army’s Office of Race Relations and Equal Opportunity toward the end of his career.

And this is a good thing, to be sure, but I read that and wondered whether minds can be changed without Black men having to throw themselves onto grenades.

Olive wound up in the Army as an alternative to being hunted by the KKK.

Early on, his grandparents had stepped in to help Olive’s widowed father, raising Olive in the Englewood section of Chicago. He was “a privileged child,” Olive’s cousin, Chinta Strausberg, wrote, with a father who bought him suits and cameras. The elder Olive had been a professional photographer, among other jobs, and taught Milton the craft.

Olive became bored with high school and ran away to his paternal grandparents’ farm in Lexington, Mississippi, attending an all-Black school there.

In 1964, he joined Freedom Summer, a movement to register Black voters. Volunteers lobbied against discrimination in the form of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other machinations designed to keep Black voters from casting ballots. They also fought against intimidation from the likes of the KKK, law enforcement, and racist locals.

Olive’s involvement in Freedom Summer terrified his grandmother. Nine years earlier, another Black teenager had come to Mississippi from Chicago. Emmett Till never made it back. And in June, three Freedom Summer volunteers went missing, their beaten bodies found six weeks later; a KKK lynch mob had killed them, aided by a coverup from a deputy sheriff who was also a Klansman.

Olive’s grandmother called his father, Strausberg wrote, who in turn called Olive and gave him three choices: go back to school, get a job, or join the military. Upon learning that his school credits from Mississippi wouldn’t transfer to Chicago and he’d have to redo 10th grade, Olive enlisted.

By all accounts, Olive loved the Army. He’d come home on leave and remain in uniform. In the summer of 1965, he wrote a letter to his cousin Barbara and light-heartedly boasted about becoming a “Sky Soldier.”

“You said I was crazy for joining up,” Olive wrote. “Well, I’ve gone you one better. I’m now an official U.S. Army Paratrooper. How does that grab you? I’ve made six jumps already.”

He was injured on one jump and was awarded a Purple Heart, went home, and insisted he needed to get back to Vietnam.

He also wrote letters to a girlfriend or a crush, Strausberg told the Tribune. A fellow soldier helped him draft those. He didn’t curse or drink, he shared his cigarette rations, listened to country music on a transistor radio, and took photos. He also carried around a Bible and earned the nickname “Preacher” in Vietnam. At home, he was known as Skipper.

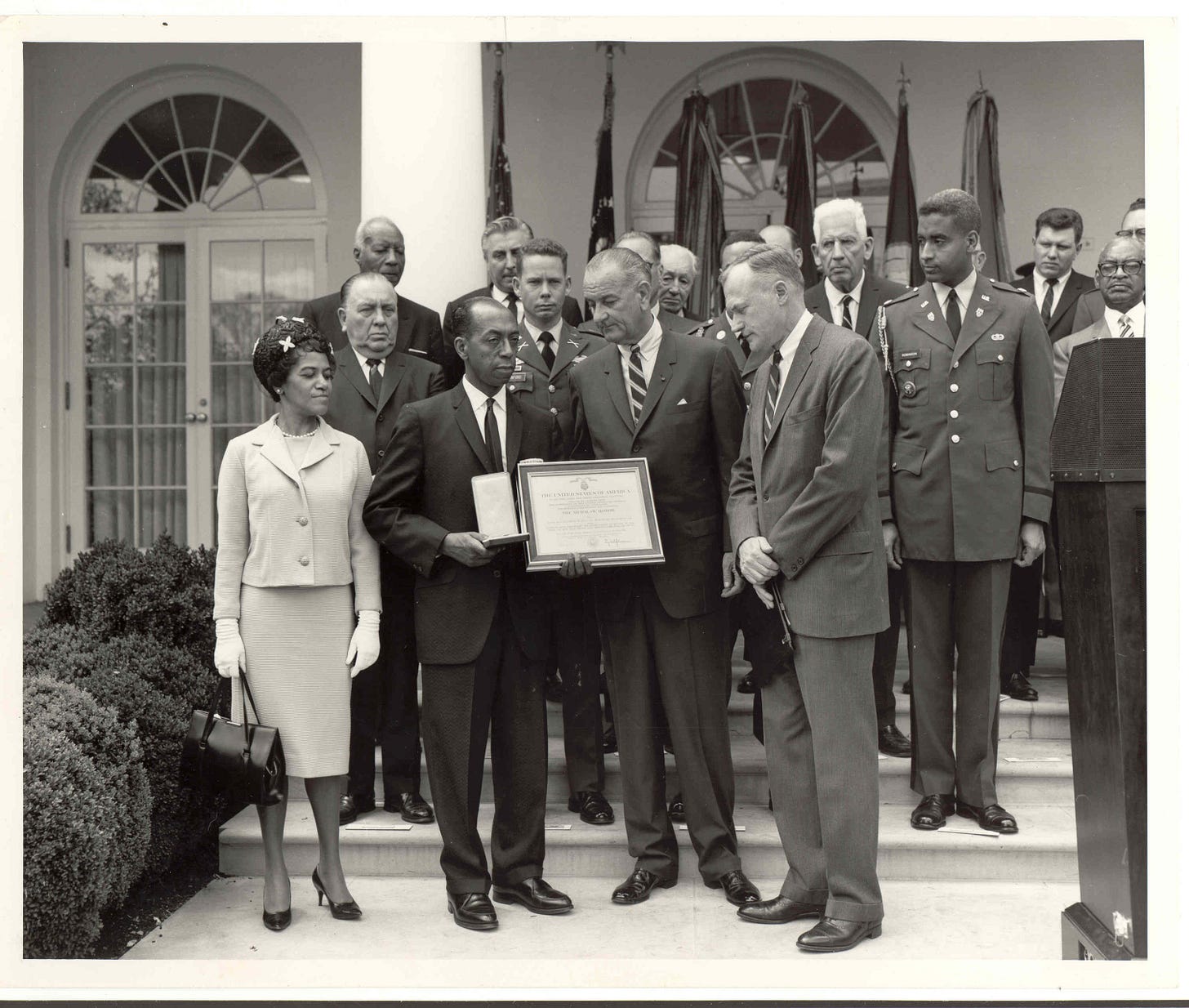

During a ceremony awarding Olive the Congressional Medal of Honor in April 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Olive’s father and stepmother, Antoinette, with the medal and a plaque. Johnson said the usual, about how the nation would never forget Milton Olive, about bravery and loyalty and how Olive was compelled by something more than duty.

“In that incredibly brief moment of decision in which he decided to die, he put others first and himself last,” Johnson said. “I have always believed that to be the hardest, but the highest, decision that any man is ever called upon to make. In dying, Private Milton Olive taught those of us who remain how we ought to live.”

But then Johnson said something I found even more interesting:

“I have never understood how men can ever glorify war. ‘The rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’ has always been for me better poetry than philosophy. When war is foisted upon us as a cruel recourse by men who choose force to advance policy, and must, therefore, be resisted, only the irrational or the callous, and only those untouched by the suffering that accompanies war, can revel.”

I have never understood how men can ever glorify war. ‘The rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’ has always been for me better poetry than philosophy.

Olive is buried at tiny West Grove Baptist Church Cemetery in Lexington, Mississippi, a town of about 1,600 people today—and whose police department just this week came under investigation by the Department of Justice for civil rights violations. The town’s former police chief, Sam Dobbins, was allegedly caught on tape bragging about killing 13 people in the line of duty, including one story in which he claimed to have shot a Black man 119 times.

It's an understatement to say Olive’s grandmother was right to be worried back in 1964.

I still want that movie for Olive, but in the meantime, he has received other posthumous honors:

Milton L. Olive Middle School in Long Island is named for him.

Olive-Harvey College is a community college in Chicago named in honor of Olive and a fellow Chicagoan, Carmel Bernon Harvey Jr. The college has put on a stage play titled Skipper for more than thirty years.

Milton Lee Olive Park is a lakefront park in Chicago just north of Navy Pier; Olive received a 50-gun salute during the park’s dedication in 1966.

Fort Campbell’s physical fitness center is named for Olive.

A civic building at Walden Chapel United Methodist Church is named the Milton Olive Center.

A monument adorns the lawn of the Holmes County Courthouse Square in Lexington, Miss., dedicated on July 4, 2017, during “Milton Olive Day.”

Vincent Yrineo kept Olive’s damaged dog tag, and Stanford pledged to tell his story for the rest of his life, as did other soldiers who served with Olive.

Olive’s father wanted to make sure no one forgot his son. He told stories for hours at family reunions and at holidays, according to Strausberg, and he called her in 1993, a couple of months before he died, to urge her to continue spreading the message.

"I think he remembered the three choices he gave his son — to either go to school, go to work or into the military,” Strausberg told the Chicago Tribune. “I think he grieved himself to death. The only peace he could find would be in making sure his son's story remains alive."

Yet another great piece! I wish everyone in the country could read about the bravery and selflessness of Milton Lee Olive III.

Such a wonderful account of a humble man who achieved great things by his sacrifice for others. We need more Olive’s in the world. Thanks for bringing out his story. You are a wonderful writer.