I Want to be Like Norman Lear When I Grow Up

Lear gave us openings to talk about difficult subjects. We need that more than ever.

There we were, smug and self-satisfied, lobbing labels onto my friend’s father.

He’s Archie Bunker.

With a shake of the head and an eye roll, we were confident in our appraisal that, for whatever faults we might have, at least we weren’t Archie.

Oh, teenagers. Meatheads, the lot of us.

It was the ‘80s, and we knew nothing about implicit or unconscious bias, or the ways racism and bigotry could slide unnoticed into a person’s life. Especially into the lives of two people who grew up in a town of 5,000 mostly white people and 10,000 pairs of shitkickers.

All we knew was that Archie clung to his stereotypes and tossed epithets around. My friend’s out-of-state father could sometimes be that way too. But not us. We didn’t use epithets or slurs. (Of course, we didn’t call him out, either. But what was the point? We were taught that some people were never going to change.)

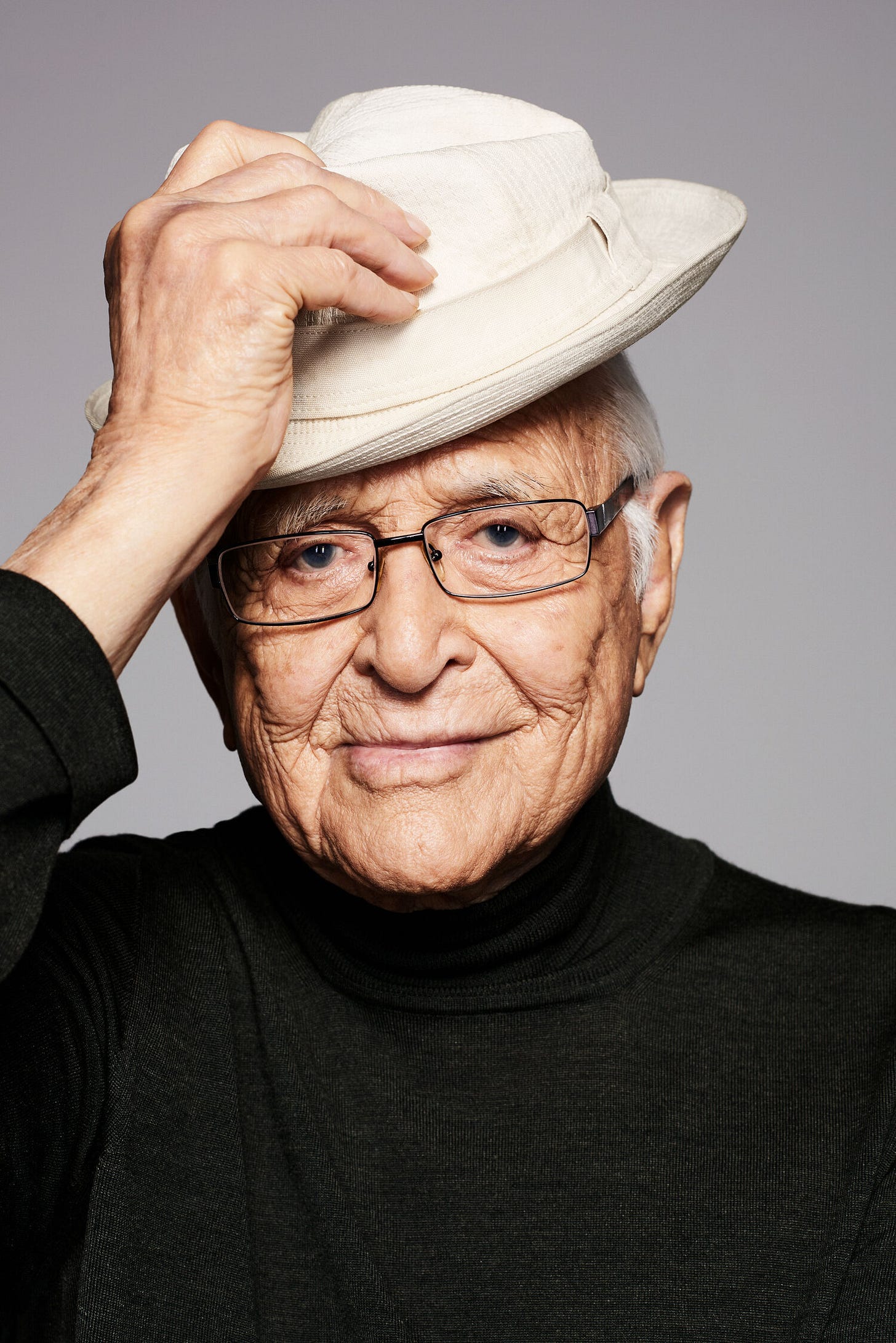

I found myself thinking about those occasional Archie Bunker conversations upon learning of the death of Norman Lear on Wednesday. Lear, who lived to be 101, was arguably the most influential television writer and producer ever, the driving force behind 1970s and 1980s shows All In The Family, The Jeffersons, Good Times, Sanford and Son, One Day at a Time, and Maude.

Such was the genius of Lear, or a sliver of his genius, that I could reflect upon a TV show that aired nearly fifty years ago and still find something to learn. (Here’s a great tribute video to Lear.)

I thought about my own teenaged certainties regarding racism (or what I thought was the lack thereof), about the Archie-Meathead relationship, about our current inability to talk with each other about difficult subjects, and the ways Lear might guide us toward finding our way back into those conversations.

“Like a sitcom,” the AP obituary read, “(Lear’s) family life was full of quirks and grudges, ‘a group of people living at the ends of their nerves and the tops of their lungs,’ he explained during a 2004 appearance at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston.”

Living at the ends of their nerves and the tops of their lungs.

Sound familiar?

Archie and Meathead—Archie’s nickname for his liberal son-in-law, Michael, played by Rob Reiner—spent a lot of their time shouting at each other. I was a young kid who didn’t see a lot of episodes, but I don’t recall them finding much common ground that way.

It’s easy to point at Archie and swear we’ll never be like him. But I couldn’t help but feel that Michael, who was on the right side of history, nevertheless wasn’t all that likable.

Ah, complexities.

Archie and Meathead spent a lot of their time shouting at each other. I was a young kid who didn’t see a lot of episodes, but I don’t recall them finding much common ground that way.

Archie was easy to dismiss and easy to laugh at, which some viewers didn’t appreciate. The New York Times obituary pointed out that critics thought the character of Archie Bunker “made narrow-mindedness seem appealing.” Two of the lead actors on the show Good Times, which starred a Black family, quit after a handful of seasons; Esther Rolle and John Amos thought the show focused too heavily on the character J.J. Evans (of the Dy-No-Mite! catchphrase) and his over-the-top antics.

I didn’t know any of that as a kid. I recognize today that Lear walked a fine line, one between finding the type of humor that keeps hearts open and mouths talking while also taking care not to minimize real pain and harm or reinforce stereotypes.

It’s not for me to say where that line is, but I do believe that, through sitcoms, Lear gave us an opening and a way into difficult subjects. He provided space for characters to be imperfect and for a lot of people to see themselves and others in those imperfect characters. We had a jumping-off point toward something meaningful.

Where is our jumping-off point now?

I remember once seeing a social media post that criticized then-late night talk show host Trevor Noah for making jokes about a topic the poster felt was too serious for jokes. I thought that particular criticism on that day was off target. Humor is sometimes unwarranted, but at other times it can be an effective way to bring people into a conversation. And if Noah could gather a bunch of people with his disarming approach, wouldn’t that be good?

To put it bluntly, I think Trevor Noah is probably more effective at changing minds than Meathead.

Or, to borrow a metaphor from author Anand Giridharadas, who wrote The Persuaders, if we want more people to get onto the highway, shouldn’t we build more on-ramps?

Norman Lear built a lot of on-ramps. I’d like to build however many my abilities allow me to build. Not through comedy—good Lord, that’s its own specialty and too dicey for me anyway.

I think instead, I can help build on-ramps with stories. To invite people to see how much our stories overlap, regardless of where we came from. When I write about myself or Lear or the soldier who threw himself onto a grenade, I hope readers see the layers and the connections. I hope I can bridge some gaps between Archies and Meatheads.

Finally, a thought from an opinion piece Lear wrote last year, on the occasion of his 100th birthday.

“Those closest to me know that I try to stay forward-focused,” he wrote. “Two of my favorite words are ‘over’ and ‘next.’ It’s an attitude that has served me well through a long life of ups and downs, along with a deeply felt appreciation for the absurdity of the human condition.”

Thank you, Norman Lear, for making us laugh and for getting us to talk about our absurd human condition.

Godspeed, sir. Over and next.

I enjoy your on ramps! Your writing is very cozy.